HALLPRINT’S REMARKABLE SA SUCCESS STORY & VOLUNTEER TAGGING

Part 2

In the autumn issue David Hall provided some background on his involvement in the worldwide gamefish tagging program. The story continues…

It is well documented now throughout the western world, including Australia, that the rate at which fish are released by anglers has steadily increased over the last two decades or so. With this we have seen an escalation in interest from recreational fishers in contributing to the scientific effort by not only reporting the recapture of tagged fish, but also in actively tagging the fish that are being released.

In SA there have been two major programs involved in recreational (volunteer) tag and release. The primary program is the SAFTAG program, which is a component of the ANSA national

AUSTAG (now Fishtag Australia) program. This program was run for many years by my dear friend Marcel Vandergoot until his sad passing in 2020. It is now run by Mick Wilson and Levi Nash on a strictly volunteer and cost recovery basis. The ANSA web site provides contact details for those interested in finding out more and potentially becoming involved in the program. The primary and preferred way of becoming involved is to join an ANSA Club first. If, however, you do not wish to join an ANSA club, but wish to go tagging, you can join RecFishSA as a Citizen Science member, which also provides you with an ANSA membership.

There is a list of mostly inshore and inland target species, including mulloway, black bream, yellowtail kingfish, King George whiting, golden perch and (in season) Murray cod among others that will be explained upon joining.

Snapper cannot be tagged during the current fishery closures, but prior to this there was a significant number of snapper tagged by volunteers, including by yours truly, in my case out from Victor Harbor in the early-mid 2010s when I lived there. Among other things, this complemented research projects undertaken during the 1980s by the Department of Fisheries supervised by myself, including one memorable very long night session off Whyalla with SA Angler co-founder Shane Mensforth in which, from memory, over 80 large snapper were tagged!

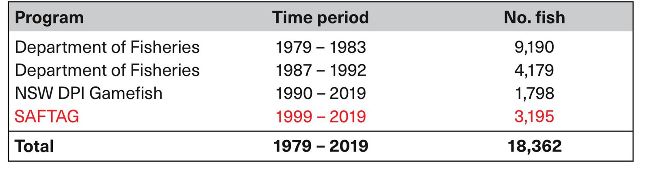

Summary of results for SAFTAG snapper tagging presented by Dr Troy Rogers.

The tagging data for snapper collected by SAFTAG were included in a study that investigated the movement of snapper in SA from tag-recapture programs (FRDC Project No.

2019-044). Dr Troy Rogers from SARDI recently summarised and presented these data to the recreational fishing community. For details, see here.

Between 1999-2019 around 3,200 snapper were tagged in SA through the SAFTAG program, with a reported recapture rate of around 8 per cent (262 fish). The data showed that 83 per cent of snapper were recaptured only short distances (less than 20km) from where they had been tagged and released. In fact, all snapper that were recaptured in Spencer Gulf were originally tagged and released in Spencer Gulf, and 97 per cent of snapper recaptured in Gulf St Vincent were originally tagged and released in Gulf St Vincent, with no movement of fish recorded between the two gulfs. However, a couple of fish released on the West Coast and one down the South-East travelled significant distances and were recaptured in Western Australia and Victoria, respectively.

RecFishSA and SAFTAG have also recently collaborated with the commercial sector with funding through the Australian Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association (ASBTIA) and FRDC to deliver a volunteer tagging project directed solely at SBT at tuna fishing tournaments. This will complement the historical tuna tagging work by CSIRO/CCSBT mentioned previously, as well as ongoing tagging of SBT through the NSW Gamefish Tagging Program founded by well-known angling identity and long-time friend, Dr. Julian Pepperell, some 50 years ago in the mid-1970s The NSW program has targeted mostly offshore and highly migratory gamefish, including SBT, whaler sharks, and yellowtail kingfish in SA waters, so there is some overlap with the SAFTAG program. Details on this program and how to become involved are here.

Another species that has yielded valuable data through volunteer tagging, both from SAFTAG and the NSW program, has been yellowtail kingfish. According to the “Project Kingfish” group of researchers from the Sydney Institute of Marine Science (SIMS), there is still very little known about the status of the ‘Eastern Australia’ kingfish population, which spans SA, VIC, TAS, NSW, QLD and NZ (see here).

A recent publication from a number of scientists across Australia and New Zealand (here) analysed data from 50 years of Australian and NZ citizen science tagging programs involving over 4,600 reported recaptures from over 63,000 tagged yellowtail kingfish (including over 45,000 from the NSW Program). This paper demonstrated a high level of stock connectivity between south-eastern states (i.e. excluding WA) with a number of recaptures of SA tagged fish from the east coast from as far north as SE Queensland. There has also been significant movement both ways across the ditch between Australia and NZ, also demonstrating that, while most movements of yellowtail kingfish are relatively localised, the biological stock may span across the two countries.

Clay Hilbert from the NSW Fisheries Game Fish Tagging Program recently advised me of another amazing report of another significant kingy recapture, which was reported after the scientific paper above was published. This recapture happened to be a first for the program and is of special relevance to SA and the movement dynamics of the species. Recaptures have shown that some kingies in Southeastern Australia (SA & VIC) will travel up the East Coast as far north as Fraser Island. While these northerly movements occur somewhat regularly, the program has never had proof of movement where a fish originally tagged on the East Coast has travelled to South Australia… until now!

A kingy originally tagged and released by Raptor Fishing Charters offshore from Sydney has been recaptured, not once, but twice in South Australia.

The fish was originally tagged by Emerson Spina on November 8, 2021 and was estimated to be over the magical 30kg mark.

After 684 days the fish was recaptured and then re-released on 23 September 2023, at Port Augusta (SA), by Shaun Ossitt. The fish had travelled over 1,150 nautical miles (~2,120 km from its original release location. Upon recapture the fish measured 142cm and was again estimated at 30kg. Only 24 days later, the fish was again recaptured by Nathan Stephens at Port Augusta. The fish was once again re-released with the original tag still in place.

Information like this on kingfish movement from tagging programs over the past 50 years has identified the need for further research to better understand the biology and ecology of this iconic species – in particular, the location of key spawning areas, movement patterns and behaviour, and how the species recruits to the coast. Such information is fundamental for effective fishery management.

The data from these long-term tagging programs have complemented the higher tech work being done by Project Kingfish with satellite tags, otolith (ear bone) biochemistry and computer modelling, just as it has for snapper and SBT.

Hallprint actually supplies arguably most of the major citizen science tagging programs world-wide, a number of which have used our tags for decades, including the very successful South African Program run by the Oceanographic Research Institute in Durban and founded by Rudy van der Elst and Bruce Mann, as well as the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences Program now run by Suzanna Musick, but established by another dear old friend, Jon Lucy. Closer to home, the SUNTAG program in Queensland, founded by close friends Bill and Shirley Sawynok, has been the major component of the AUSTAG (now Fishtag Australia) program for over 37 years now, and has accounted for an incredible 900-odd thousand out of over a million fish tagged nationally to date - here.

As at September 2024 there have been over 78,000 recaptures (7.6 per cent) to date from the Fishtag Australia (which includes SAFTAG in SA) program which, like the ORI program in South Africa, has used Hallprint tags throughout and yielded many long-term recaptures of up to 26.5 years for an impoundment bass in Queensland (a photo of the bass and the tag is shown below). This program now generates data which enables a company called Infofish (also run by Bill and Shirley) with IT support form son Stefan to produce a huge range of “dashboards” based mostly on tag and recapture information. These dashboards are of great interest to a number of parties, including fisheries managers and regional tourism and council bodies among others (Bill Sawynok pers. comm). The fact that recapture information can not only demonstrate fish movement and growth, but also reflect fisher behavioural trends over time such as fishing effort levels, release rates and gear types e.g. lure versus bait, potentially makes it a powerful tool generated by citizen scientists. An overview dashboard for Queensland is available here.

Photos of a freshwater bass and tag recaptured after 26.5 years at liberty in Somerset Dam Queensland. As you can see the tag remained very readable (photos credit Bill Sawynok & SUNTAG).

I guess you might well expect me to say this as the owner and director of Hallprint, but there remains great potential for citizen science-run volunteer tagging programs to continue the momentum and work together collaboratively across the globe to build on the foundations established by the long running programs. In 2023 a virtual Fishtag Summit, inspired and directed by Bill Sawynok, was held among existing program leaders and from this a number of advances have been made, including an international project to look at climate change driven “range shift” in species.

As our waters warm, we are seeing a southwards expansion (northern in the northern hemisphere) in the range of different species, and tagging can be a very useful tool to document the extent of these changes. This range shift also has a number of social and safety implications, including issues associated with anglers in small boats potentially going further offshore.

I remain a very active volunteer tagger myself, focused these days mostly on yellowfin whiting. We are also looking at potential new innovations, such as producing tags that can be read by mobile phones that communicate with an App, potentially removing the need to record tag numbers, location and date manually, so it is not a static field.

Hopefully, I have provided a bit of insight here into both the company that I own and direct and the use of external “conventional” fish tags by anglers and collaborating scientists in SA and elsewhere. There is much more to be done to unravel the mystery of our oceans and its important recreational fish stocks, but if I have inspired even one extra angler to genuinely get involved in tagging, then it has been worth it!

(I would like to acknowledge CSIRO Fisheries Scientist Naomi Clear for her input on the CSIRO tagging program, as well as Jonah Yick, Tuna Champions Scientific Ambassador for tuna photos and recapture information, as well as Troy Rogers, Bill Sawynok and Levi Nash for their input as described. And finally, the team at Hallprint for making it all possible, including General Manager Darren Evans and Production Manager Julie Langmead and staff, as well as my wife and business partner Leanne Berich.). And Brett Mensforth for prompting me to write this piece!

A younger Patrick Dangerfield holding a tuna tagged by the author before release back in January 2015 – on the SA Angler boat with Shane and Brett Mensforth.